It is worth mentioning, for future reference, that the creative power which bubbles so pleasantly in beginning a new book quiets down after a time, and one goes on more steadily. Doubts creep in. Then one becomes resigned. Determination not to give in, and the sense of an impending shape keep one at it more than anything. I'm a little anxious. How am I to bring off this conception? Directly one gets to work one is like a person walking, who has seen the country stretching out before. I want to write nothing in this book that I don't enjoy writing. Yet writing is always difficult. Virginia Woolf, A Writer's Diary, Edited and with an Introduction by Leonard Woolf

|

Tuesday, May 11th [1920]

It is worth mentioning, for future reference, that the creative power which bubbles so pleasantly in beginning a new book quiets down after a time, and one goes on more steadily. Doubts creep in. Then one becomes resigned. Determination not to give in, and the sense of an impending shape keep one at it more than anything. I'm a little anxious. How am I to bring off this conception? Directly one gets to work one is like a person walking, who has seen the country stretching out before. I want to write nothing in this book that I don't enjoy writing. Yet writing is always difficult. Virginia Woolf, A Writer's Diary, Edited and with an Introduction by Leonard Woolf Sunday, March 18th [1928]

I have lost my writing board; an excuse for the anaemic state of this book. Indeed I only write now, in between letters, to say that Orlando was finished yesterday as the clock struck one. Anyhow the canvas is covered. There will be three months of close work needed, imperatively, before it can be printed; for I have scrambled and splashed and the canvas shows through in a thousand places. But it is a serene, accomplished feeling, to write, even provisionally, the End, and we go off on Saturday, with my mind appeased. Virginia Woolf, A Writer's Diary, Edited and with an Introduction by Leonard Woolf Two days ago – Sunday 16th April 1939 to be precise – Nessa said that if I did not start writing my memoirs I should soon be too old. I should be eighty-five, and should have forgotten – witness the unhappy case of Lady Strachey. As it happens that I am sick of writing Roger’s life, perhaps I will spend two or three mornings making a sketch. There are several difficulties. In the first place, the enormous number of things I can remember; in the second, the number of different ways in which memoirs can be written. As a great memoir reader, I know many different ways. But if I begin to go through them and to analyse them and their merits and faults, the mornings – I cannot take more than two or three at most – will be gone. So without stopping to choose my way, in the sure and certain knowledge that it will find itself – or if not it will not matter – I begin: the first memory. Virginia Woolf, A Sketch of the Past, in Moments of Being Virginia Woolf Unpublished Autobiographical Writings, Edited and with an Introduction and Notes by Jeanne Schulkind.

But, you may say, we asked you to speak about women and fiction – what has that got to do with a room of one’s own? I will try to explain. When you asked me to speak about women and fiction I sat down on the banks of a river and began to wonder what the words meant. They might mean simply a few remarks about Fanny Burney; a few more about Jane Austen; a tribute to the Brontës and a sketch of Haworth Parsonage under snow; some witticisms if possible about Miss Mitford; a respectful allusion to George Eliot; a reference to Mrs. Gaskell and one would have done. But at second sight the words seemed not so simple. The title women and fiction might mean, and you may have meant it to mean, women and what they are like; or it might mean women and the fiction that is written about them; or it might mean that somehow all three are inextricably mixed together and you want me to consider them in that light. But when I began to consider the subject in this last way, which seemed the most interesting, I soon saw that it had one fatal drawback. I should never be able to come to a conclusion. I should never be able to fulfil what is, I understand, the first duty of a lecturer – to hand you after an hour’s discourse a nugget of pure truth to wrap up between the pages of your notebooks and keep on the mantelpiece for ever. All I could do was to offer you an opinion upon one minor point – a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction; and that, as you will see, leaves the great problem of the true nature of woman and the true nature of fiction unsolved. I have shirked the duty of coming to a conclusion upon these two questions – women and fiction remain, so far as I am concerned, unsolved problems. But in order to make some amends I am going to do what I can to show you how I arrived at this opinion about the room and the money. I am going to develop in your presence as fully and freely as I can the train of thought which led me to think this. Perhaps if I lay bare the ideas, the prejudices, that lie behind this statement you will find that they have some bearing upon women and some upon fiction. At any rate, when a subject is highly controversial – and any question about sex is that – one cannot hope to tell the truth. One can only show how one came to hold whatever opinion one does hold. One can only give one’s audience the chance of drawing their own conclusions as they observe the limitations, the prejudices, the idiosyncrasies of the speaker. Fiction here is likely to contain more truth than fact. Therefore I propose, making use of all the liberties and licences of a novelist, to tell you the story of the two days that preceded my coming here – how, bowed down by the weight of the subject which you have laid upon my shoulders, I pondered it, and made it work in and out of my daily life. I need not say that what I am about to describe has no existence; Oxbridge is an invention; so is Fernham; “I” is only a convenient term for somebody who has no real being. Lies will flow from my lips, but there may perhaps be some truth mixed up with them; it is for you to seek out this truth and to decide whether any part of it is worth keeping. If not, you will of course throw the whole of it into the wastepaper basket and forget all about it. Virginia Woolf, A Room of One's Own. Photo taken in Providence Public Library.

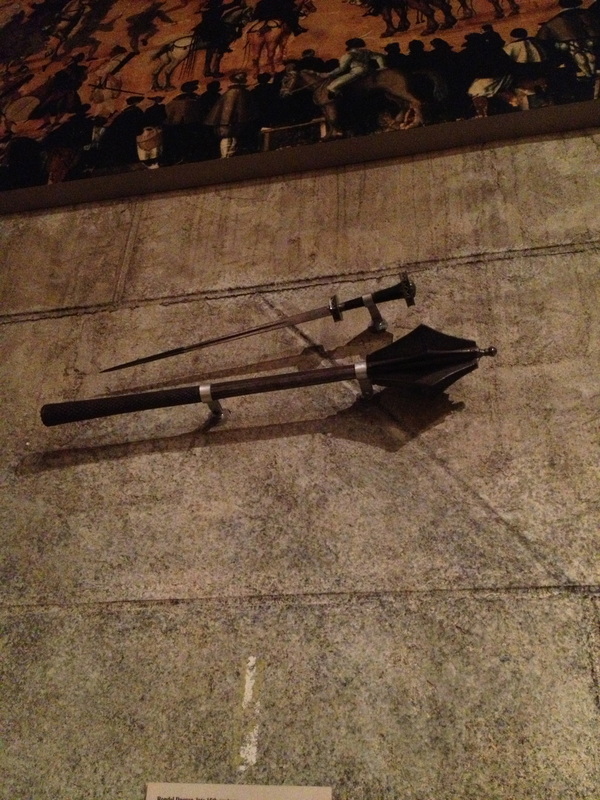

Your mother was born in 1879, and as some six years at least must have passed before I knew that she was my sister, I can say nothing of that time. A photograph is the best token there is of her appearance, and the face in this instance shows also much of the character. You see the soft, dreamy and almost melancholy expression of the eyes; and it may not be fanciful to discover some kind of test and rejection in them as though, even then, she considered the thing she saw, and did not always find what she needed in it. But certainly it would be mere fancy to conceive that this was other than unconscious at that age. For the rest, a mother who gazed in her face might feel her heart leap at the endowment already promised her daughter, for she was to have great beauty. And in this case the mother would also feel tender joy within her, and some bright amusement too, for already her daughter promised to be honest and loving; already, as I have heard, she was able to care for the three little creatures who were younger than she was, teaching Thoby his letters, and giving up to him her bottle. I can imagine that she attached great importance to the way in which Thoby sat in his highchair, and appealed to Nurse to have him properly fastened there before he was allowed to eat his porridge. Her mother would smile silently at this. Virginia Woolf, Reminiscences, Chapter One, in Moments of Being Virginia Woolf Unpublished Autobiographical Writings. Edited and with an Introduction and Notes by Jeanne Schulkind. Photo taken in Higgins Armory Museum, Worcester, MA.

|

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed